Like so many things that cycle in popularity, food gardening is again in vogue. For most Americans, the vegetables and fruits they harvest from their backyard gardens supplement the food they purchase at the supermarket. Gardeners take great pride in their homegrown bounty, but few need to rely on it for basic sustenance.

That wasn't always the case. During World Wars I and II, food gardening wasn't merely an enjoyable pastime, it was necessary for survival. And the gardens weren't limited to family backyards. Businesses and schools dedicated space for growing food, and public parks were cultivated to create hundreds of garden plots. Communities came together to grow, tend, and harvest, and the bounty of these "Victory Gardens," as they came to be known, was shared by all.

Garden to Give: Inspiring Gardeners to Help Feed the Hungry

That same spirit of community has inspired the "Garden to Give" movement. Spearheaded by Gardener's Supply Company, Garden to Give encourages gardeners to donate their extra produce to their local food pantries to help feed the hungry in their communities. By one estimate, gardeners could feed 28 million hungry Americans just by donating the extra produce they already grow. Some individuals, community groups and schools are taking it a step further and planting special "giving gardens" so they'll have even more fresh produce to donate! Some are even referring to these gardens as Victory Gardens. Scroll down to "Start Your Own Victory Garden" for tips on planning a school Victory Garden, including consulting with your local food pantry for their recommendations on what to grow and the best times to drop off donations.

The Story of Victory Gardens

The values inherent in the wartime Victory Garden movement are making a comeback, including thriftiness, self-reliance, an awareness of where one's food originates, and the potential for gardening to bring communities together. The evolution of the Victory Garden concept is a fascinating story and yields important lessons about the impact individuals and groups can have in ensuring all of us have access to the fresh fruits and vegetables that support good health. The story is also a wake-up call that the skills of food growing, the conservation of land suitable for cultivation, and the willingness of communities to work together for the common good are all vital to practice, and to pass on from generation to generation.

The Migration from Rural to Urban

Until the early 1900s, a majority of Americans lived in the countryside and were relatively self-sufficient. Most households had large food gardens, and the vegetables, fruits, and herbs grown in them supplied much of each family’s dietary needs.

The early 1900s brought rapid advancements in technology that led to a shift in manufacturing from small, home-based “cottage industries” to mass production at large factories. Many Americans migrated from rural areas to cities, lured by the notion that year-round manufacturing jobs would bring better wages than seasonal farm labor. Long work hours and crowded urban dwellings left little time or space for food gardens. By 1920, only fifty percent of Americans lived in rural areas. For the most part, growing food was left to farmers.

The Outbreak of War

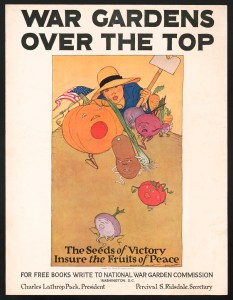

In early 1917, prior to the U.S. entering what was then called The Great War ("the war to end all wars," later known as World War I), multi-millionaire Charles Lathrop Pack launched the "War Garden" campaign. The conflict was causing devastating food shortages in Europe, and Pack realized that American farm-produced food was desperately needed overseas to feed both Allied troops and starving civilians. In response, Pack sought to support the war effort and stave off food shortages at home by encouraging all Americans — not just farmers — to start growing food. This would free up commercially grown food to be shipped overseas. The National War Garden Commission was established in March 1917. Just a month later, the U.S. entered the war.

The War Garden Commission launched an all-out public relations campaign to promote food gardening at private residences and public lands — every patch of soil was a potential garden site. They distributed a wealth of colorful posters exalting citizens to “Sow the Seeds of Victory” and created educational materials for new gardeners. Local governments and community groups rallied in support of the cause. Growing a War Garden became a sign of patriotism, and it boosted morale by giving civilians a tangible way to contribute to the war effort.

Food gardens sprouted up everywhere — backyards, municipal parks, empty lots, city rooftops. Private companies set aside land for employee gardens. Urban dwellers sowed seeds in planters and window boxes.

The federal Bureau of Education launched the United States School Garden Army (USSGA) to enlist schoolchildren in the cause, dubbing them “soil soldiers” in the “home garden army.”

School grounds were tilled, planted, tended, and harvested by students and their teachers. The USSGA motto — "A garden for every child, every child in a garden" — drove home the point that every American, of every age, could make an important contribution to the country's wellbeing.

More than five million War Gardens were cultivated in 1918, producing vegetables and fruits worth over a half-billion dollars. With further encouragement and how-to advice from the government, much of that food was canned, pickled, or dried for future use.

Even after the 1918 Armistice that signaled the end of the war, the government still encouraged citizens to cultivate food gardens. Farm-grown food could be shipped overseas to help feed the millions of people there who faced starvation due to the loss of so many farmers-turned-soldiers, as well as the devastation of farmland that was ravaged by the violent battles fought there. These post-War gardens became known as "Victory Gardens." Eventually, the fervor of the War Garden campaign waned, and America’s enthusiasm for home food gardening waned as well.

The Second World War

In 1941, just 24 years after the signing of the Armistice, the U.S. was drawn back into war. Once again there was a strain on domestic food supplies as the country was faced with shipping large quantities of food overseas to feed troops. Based on the success of the earlier War Garden campaign, the U.S. government began a similar but even more fervent propaganda campaign, dubbing it "Food for Victory."

The new public relations campaign was overt in its message: Growing food was a patriotic duty. The more food that was grown in Victory Gardens, the closer America would be to winning the war. Eleanor Roosevelt set an example by planting a Victory Garden on the White House grounds. And when food rationing began in 1942, Americans had even more incentive to start growing their own vegetables and fruits.

Once again the government produced posters and other materials exhorting all citizens to do their duty in support of the war effort. Local governments gave workshops and distributed how-to information to new gardeners. Detailed guidelines showed gardeners how to plan for the maximum harvest — which crops had the highest yields, had the most nutrients, and were the easiest to grow. Among the recommended crops were kohlrabi and Swiss chard — both of which were unfamiliar to most American gardeners at the time. Succession planting was recommended so that gardens could be productive from spring into late fall.

Americans rallied. Front lawns were tilled; flower gardens replanted with vegetables. Urban parks, including Golden Gate Park and Boston Commons, became home to hundreds of food garden plots tended by both individuals and local groups. New gardening tools were hard to come by because steel was being diverted to munitions manufacturers, so families and neighbors shared shovels and hoes. Gardening in public spaces brought communities together for a common cause.

By 1944, there were more than 20 million Victory Gardens that produced more than a third of all the fresh vegetables grown in the U.S. Homegrown food not only provided much-needed sustenance during food rationing, it also meant that less food had to be trucked long distances from farms to markets, reducing fuel consumption and conserving the rubber needed for tires — both important commodities in the war effort.

Victory Gardens in the Post-War Years

Once again, after the war ended the fervor and support of government and community groups declined, and for many Americans, so did the passion for growing food. Inexpensive, easy-to-make packaged foods became attractive alternatives to time spent toiling in the garden and preparing meals from scratch. That said, gardening continually ranks high in the list of most popular hobbies. And the value we place on fresh, homegrown and locally produced food is continuing to rise. Community gardens have long waiting lists for plots. Farmer's markets sprout on urban and suburban street corners.

Start your Own Victory Garden

By cultivating home, school, and community gardens, parents and educators are helping kids understand where fruits and vegetables come from — before supermarkets wrap them in plastic or package them onto Styrofoam trays. Kids get to experience the satisfying crunch of a freshly pulled carrot and the excitement of picking the first vine-ripened tomato. These experiences can have lasting effects by inspiring youth to understand and pursue healthy eating habits. For some youth, a lifelong hobby of food gardening will take root in these early experiences!

Before you begin expanding your garden to grow more than you need, first locate a local food shelf or food pantry that can help you find a good home for any extra fruits and vegetables. AmpleHarvest.org is a good place to begin your search. There are a wide variety of community organizations that provide food assistance, but sometimes it takes a little big of digging to find an organization able to distribute perishable food items like fruits and vegetables.

Once you locate an organization to work with, ask them for a wish list of fruits and vegetables, and also what days are best for them to accept donations. Some facilities may have limitations in storage (especially cold or cool storage). They also may only distribute food on certain days of the week and so you will want to harvest your produce as close to those dates as possible. Ask them what fruits and vegetables they think their clients are most likely to use and enjoy. Unusual fruits and vegetables may be fun to grow, but they may also be intimidating to those not use to cooking with them. Ask if there any other food handling guidelines you should follow when harvesting.